"I have been lucky enough to visit many excavations over the

years, but rarely has the past felt closer than that morning in Must Farm

quarry."

Dr Matthew Symonds (Editor Current Archaeology)

Must Farm is, quite simply, unique. 150 years ago, the flat Fenland landscape stretched far to the horizon, dotted with trees and villages, crops and cattle. Yet beneath it was hiding an archaeological treasure-trove waiting to be discovered.

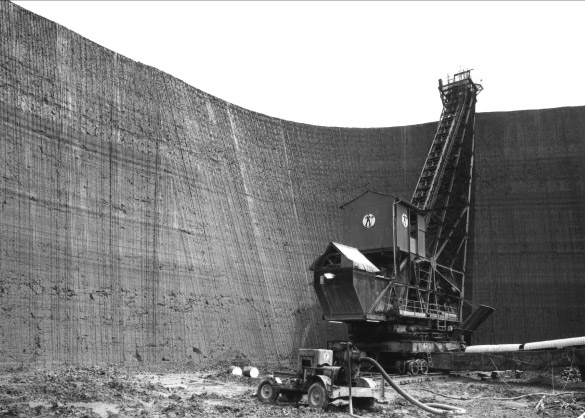

The first hint was revealed when the Victorian demand for bricks prompted companies in and around Must Farm to start excavating the local clay. Not normal clay, but Lower Oxford Clay, a clay rich in carbonaceous material that ignites during the firing process to produce bricks of a finer quality.

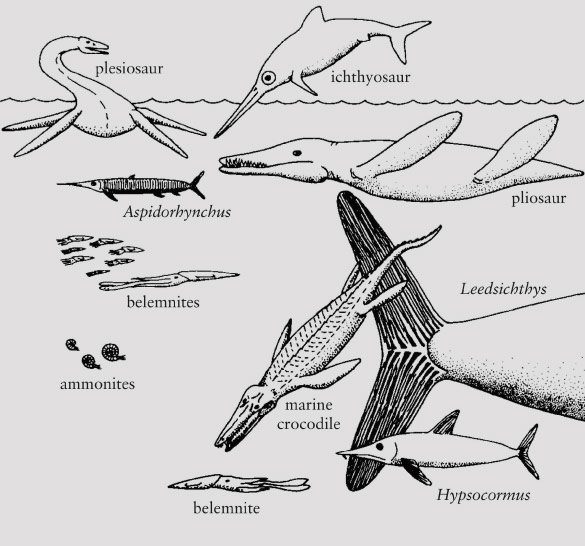

Importantly for Must Farm, Lower Oxford Clay as the name might suggest is found deep under the surface and in the process of extracting it, fossilised bones were discovered. The bones of dinosaurs.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a local farmer Alfred Nicholson Leeds perfected methods of extracting the dinosaur fossils from the soft clay, meticulously recording the parts of each skeleton, and piecing together the broken fragments at home.

In the process, he discovered new species, expanded the understanding of species already known, and his magnificent finds can still be seen in the British Museum and other museums in Germany, Austria, and North America.

Enter the Bronze Age

Our interest in Alfred Nicholson Leeds is less about dinosaur fossils and more about the relationship between the vertical and horizontal scale of the brick pits. In particular, the opportunity they afford to explore an entire landscape at depth.

For, just as the extraction of the Oxford clay enabled access to dinosaur fossils at a depth of around 30 metres, so it has enabled access to deeply buried Neolithic and Bronze Age landscapes. Artefacts closer to the surface and, therefore, closer to us in time.

In the summer of 1999, decaying timbers were discovered protruding from the southern face of the quarry pit at Must Farm. Subsequent investigations in 2004 and 2006 dated the timbers to the Bronze Age and identified them as a succession of large structures spanning an ancient watercourse.

Crucially for Must Farm, the timber structures were wet when they were built, wet during their use, and wet for a long period afterwards. Uncomfortable, perhaps, for our Bronze Age ancestors, but of huge interest to us because the environment was ideal for preservation.

So began what has become one of the most important Bronze Age discoveries in Europe.