Post-Ex Diary 5: Context and Deposition

August 6, 2018

When archaeologists typically excavate a site, they encounter the residue of an occupation. At most settlement sites, the people who resided there could have done so for years, even over multiple generations. The material deposited there accumulated over time and as sites became abandoned it is rare for their contents to be left in any semblance of the day-to-day lives of their occupants. When material from most sites can be dated, habitation can normally only be narrowed down to decade or half-century windows, especially during prehistory.

The Must Farm settlement’s destruction raises questions about whether this material reflects its position prior to the fire that brought about the end of the site. Recent post-excavation work is helping us to address that issue and revealing some insights about the settlement’s surroundings.

At Must Farm the preservation of the material left behind is fantastic because of the ideal combination of charring and waterlogging. Textiles, wooden objects and environmental evidence are among the finest examples from the Late Bronze Age found in Britain. However, just as important is the outstanding preservation of the original contextual detail.

Archaeology is just as much about the context of objects as the artefacts themselves. A beautiful socketed axe is an incredible find but being able to know where that item would originally have been kept is immensely valuable. Analysing and understanding the spatial story of the Must Farm settlement is a crucial element of the project and tantalising details are beginning to emerge during our post-excavation assessment.

In-situ Late Bronze Age socketed axe. In archaeology understanding the context of objects is as important as the artefacts themselves.

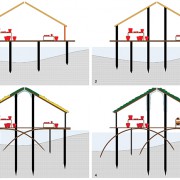

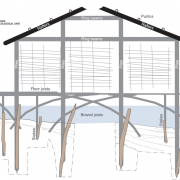

However, the nature of the Must Farm structures themselves have made us carefully examine the distribution of material from the excavation. The buildings at the site were stilted, situated above a river channel and destroyed by an intense fire. When excavating, we were not encountering the preserved interiors of buildings as they no longer existed. Instead we were digging the layers created because of the settlement’s destruction. Yet, there were obvious signs of patterns amongst the material we were encountering that suggested a strong correlation between objects and their original positions within the Must Farm structures.

Material Distribution and Environmental Conditions

During the excavation we described how we felt the material at the base of the river channel had not travelled far from where it would have fallen (see Dig Diary 26: Exploring Inside a Bronze Age Home). Initial environmental evidence seemed to support this notion as it suggested that the river channel was shallow and slow moving. During our post-excavation work we have discovered further interesting information that has shed more light on the character of the river channel and exactly why the material has retained its original positioning from within the stilted buildings.

Throughout 2017 work was being carried out exploring the environmental evidence collected during the excavation. Analysing a variety of samples for pollen data, plant remains and examining the channel’s geomorphology has provided a more detailed understanding of the river channel. While we suspected that the river was sluggish and shallow, the environmental data suggests that at times it may have been almost dry.

Having studied the plant remains and related evidence it appears the river channel had dense reeds along its course and, importantly, underneath the structures. We suspect that these created a “hairbrush” effect, catching artefacts and debris as the structures burned and their floors collapsed. This slowed material as it was deposited into the channel, helping to keep fragile objects, such as pottery, from breaking. Additionally, it helped artefacts remain consistent with their original positions inside the structures, simply dropping them directly below the footprints of the stilted buildings. Post-excavation analysis of the environmental data has allowed this additional level of detail to help refine our understanding of how materials came to rest in their current positions.

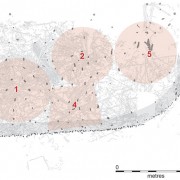

More detailed knowledge of the seasonal conditions of the river itself have also enabled us to explore the surrounding environment at different stages of the site’s short lifespan. The fact that the river appears to have been seasonally extremely shallow, or even occasionally dried out entirely, offers interesting insight into the construction of the structures and the palisade. During the excavation we encountered preserved footprints, particularly surrounding the palisade. It seems very likely that these groups of footprints were the result of people involved in the construction of the palisade during a time when the river was dry or shallow.

It is clear drier conditions would be far better building conditions and the still-damp mud surrounding the site captured impressions of the peoples’ feet as they worked. Interestingly, animal hoofprints are present alongside the footprints suggesting the presence of various species at the site during the construction. It is an amazing glimpse of a very specific moment in the creation of the palisade over 3,000 years ago and really helps connect us to the people involved in the creation of the Must Farm dwellings.

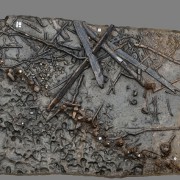

A drier construction environment also helps us better understand the quantities of woodchips and other associated debris present at the bottom of the river channel. Initially, we believed the river to be so shallow and slow-moving that it was almost still. This seemed to explain why so many woodchips still surrounded the palisade and the pile-dwellings’ posts. However, much of the construction debris seemed to be directly in situ as opposed to having sunk close to where it originated.

Dry, though muddy, conditions account for the positions of the woodchips far more convincingly. This means that the spatial distribution of the construction material, particularly clusters of woodchips, could potentially reveal interesting information about the creation of the palisade. The fact we can now be relatively confident in their positions means further fine-grained analysis is being explored. Though small, woodchips can provide insight into construction practices particularly in the species of wood, how they are cut/formed and where within a piece of wood they originated from.

Exploring Artefact Distribution

Through post-excavation we have been able to further explore and refine our working theories on the distribution of the material at the Must Farm settlement. With a better understanding of the environmental conditions, gained using a variety of scientific analyses, we can be more confident in our interpretations. So, despite the artefacts not being in their original context, their positions are representative of where they would have been located prior to the destruction of the structures.

The pottery refitting exercise in progress. We’ll be talking about refitting, and what it can tell us, in more depth in our next update.

Knowing this, the next stage of work is to begin exploring the material in much greater detail to identify patterns and differences across the site. We are currently carrying out refitting exercises using different artefact types, such as ceramics and animal remains, to see if we can reconnect broken pot sherds and match different bones together. This is no easy task given the thousands of fragments we have recovered! In our next blog post we’ll go into more detail on the refitting activities and begin to outline some of the details that are emerging.

Related stories

Post Ex-Diary 22: Working Towards Publication

May 11, 2020

Post Ex-Diary 21: The Importance of Visualisation – Photography Part Two

February 17, 2020

Post-Ex Diary 19: The Importance of Visualisation – Illustration

December 9, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 18: The Importance of Visualisation – Photogrammetry

November 11, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 17: Stable Isotope Analyses and Must Farm

October 7, 2019

Post Ex-Diary 16: Parasites and Lifestyles at Must Farm

September 3, 2019

Post Ex-Diary 15: Exploring Structure 4 Part Two

August 5, 2019

Post Ex-Diary 14: Exploring Structure 4 Part One

July 15, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 13: The Must Farm Pile-Dwelling Settlement Open Access Antiquity Article

June 12, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 11: The Must Farm Textiles Part One

April 1, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 10: Specialist Analyses Part Three

March 4, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 9: Specialist Analyses Part Two

February 4, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 8: Specialist Analyses Part One

January 7, 2019

Post-Ex Diary 7: The Must Farm Pottery Refit

November 5, 2018

Learn more

About

The Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement was excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit with funding from Historic England and Forterra.Publications

Read the Open Access publications the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement: Volume 1. Landscape, architecture and occupation and Volume 2. Specialist reports.Dig Diaries

The excavation of the Must Farm settlement was carried out between August 2015 and August 2016. Take a look at our diary entries documenting the excavation process. ...read more

Discoveries

See some of the discoveries from the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement.

Making Must Farm

Find out about our work with AncientCraft recreating Must Farm’s material.

FAQs

Further information on the Must Farm project.