Dig Diary 19: Discovering Britain’s Oldest, Complete Wheel

February 29, 2016

The Western Area and A Later Bronze Age Wheel

Over the course of the Must Farm project the excavation has constantly surprised us, both in terms of its preservation and the amazing variety of artefacts present. A few weeks ago, we had absolutely no idea that sitting underneath the river sediment would be yet another fascinating piece of Bronze Age technology: a complete wheel. It only goes to show how hard it is to try and predict what archaeology we may encounter: even in our most optimistic dreams we never expected to find part of a vehicle!

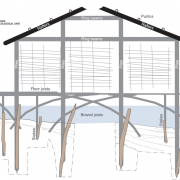

Our site is broken into three key areas: a central area containing most of our clearly defined houses, a small eastern area with part of the palisade running across it and, lastly, a western area with a mixture of palisade and burnt, structural timbers. Most of the focus of the excavation so far has concentrated on this central portion, that was initially divided into quadrants. Recently, we began to move a smaller team into the western area of site to begin to explore what appears to be part of another house.

Overview shot showing the western area of the site

The western area of site has generally poorer wood preservation than the central section of the site. This is most likely a result of it being closer to the quarry edge when it was open during the last century. Water would have drained more easily resulting in less waterlogging to help keep the timbers from beginning to decay. As we were working on removing the sediments using the same methods as the centre of the site, we started to uncover timbers that showed evidence of degradation.

Once we reached the river sediments around the wood layer, we noticed an unusual piece of timber and began to clean around it, defining an object. It became clear that this was something special and we soon realised that it was a wheel with a design very familiar for the Later Bronze Age. The wheel had suffered from some decay owing to its position in this area of site but was fortunately still in surprisingly good condition. At this stage our wood specialists gave the object an initial examination which revealed some very interesting details.

Examining “The Whittlesey Wheel”

Close-up of the axle of the wheel which is made from oak

The wheel itself is “tripartite” in its construction: the body of the object is made from three large wooden boards. At the moment we don’t know what the wood used for the main part of the wheel is. The condition of the timber is not good enough for a visual identification, so samples will have to be taken and sent away for microscopic identification by an archaeobotanist. The axle of the wheel is definitely made from oak, which was very clear thanks to visible radial structures in the wood.

In order to hold the three planks together, the wheel has two braces that sit on opposing sides at the top and bottom of the object. These are held in position with a shaped joint which, on closer examination, turned out to be a dovetail joint. At this point, we aren’t sure of the wood used for these bracers however it is likely to be a fairly softwood to make it easier to create the joint. Our complete wheel is very similar to a fragmentary one discovered at Flag Fen, showing that similar construction methods were being used across this landscape in the Later Bronze Age.

Image showing the position of the bracer held in place with a dovetail joint

There is some degradation and damage to the wheel. It has decayed slightly, losing some of its thickness: it was probably somewhere between 3-4cm thick. There is also a relatively large bore hole that has unfortunately gone through the upper portion of the wheel at some point during the 20th century before the site was discovered. So, even though it is mostly complete it still bears damage from its 3,000 years buried in the river sediments.

The wheel has two very distinct “lunate” holes to either side of the axle. These are a feature commonly seen in wheels from this period in Europe, such as a contemporary example from Federsee in Wattemberg, Germany. They probably are not just aesthetic but serve a purpose in helping to keep the wheel secured together. Interestingly, as with many other artefacts from the site, the surface of the wheel has been subjected to radiant charring. This type of charring strongly suggests that the wheel was nearby to a fire but was not directly in one. This raises interesting questions, where would this artefact have been in relation to the burning buildings to receive this kind of charring?

Close-up showing one of the lunate holes next to the axle

Why is there a wheel at Must Farm?

Perhaps the most interesting aspect to the discovery of this wheel at the Must Farm settlement is why it is here in the first place. The houses being built atop stilts over the river channel in a very wet, marshy landscape makes the presence of a wheel very surprising. We know from previous excavations that boats were one of the main methods of getting around the waterways of the Fens. So, why is there a wheel from a vehicle sitting within a river channel?

Is it possible that the wheel had perhaps been brought to the settlement to be repaired? Could it have been reused in a different way with a new function in or near one of the houses? We currently don’t have any answers to these questions. Much will rest on whether there is any more evidence of the vehicle from elsewhere within the confines of the settlement. Currently we don’t know that this is an isolated example and more of the cart could be buried deeper in the sediments around where the wheel was discovered.

Excavation of horse spine (originally believed to be from a cow).

The presence of the wheel also highlights some other interesting points. Horses are relatively uncommon in this area during the Bronze Age. It isn’t until the Middle Iron Age that horses form a much larger part of settlement sites, in terms of the animal bone evidence. A series of articulated vertebrae from elsewhere on the site were previously thought to be from a cow, but actually belong to a horse. It is probable that the vehicle the wheel is from would have been drawn by a horse, which goes against the traditional view of a Later Bronze Age settlement and its animals.

In previous weeks we have been describing the strong ties with the surrounding dryland areas and the wheel represents another facet of this. We are excavating an archetypal wetland site: a series of stilted buildings constructed over a river. Yet so much of the material present at the site is archetypally dryland in its character, whether it is the wheel or animal bone from sheep and cows.

There is still a lot of information left to investigate about the wheel. Some of this will come from samples and analysis of the object itself and more will be revealed as excavation around the artefact continues. It is yet another brilliant example of how the settlement at Must Farm continues to surprise us with truly incredible archaeology.

Related stories

Dig Diary 22: A Tour of the Excavation: Part Two

March 21, 2016

Dig Diary 21: A Tour of the Excavation: Part One

March 14, 2016

Dig Diary 20: Excavating in the Fenland Landscape

March 7, 2016

Dig Diary 19: Discovering Britain’s Oldest, Complete Wheel

February 29, 2016

Dig Diary 18: Looking Inside and Outside Roundhouse One

February 22, 2016

Dig Diary 17: Formality and the Must Farm Settlement

February 15, 2016

Dig Diary 16: Earlier and Later Periods in the Fenland Basin

February 8, 2016

Dig Diary 15: Exploring the Occupation Deposit

February 1, 2016

Learn more

About

The Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement was excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit with funding from Historic England and Forterra.Publications

Read the Open Access publications the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement: Volume 1. Landscape, architecture and occupation and Volume 2. Specialist reports.Post-Ex Diaries

Our work on-site has finished but lots more investigation is taking place as we study both the material and the evidence we recovered. ...read more

Discoveries

See some of the discoveries from the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement.

Making Must Farm

Find out about our work with AncientCraft recreating Must Farm’s material.

FAQs

Further information on the Must Farm project.