Dig Diary 28: Our Houses – What We Know and What We Don’t, Part One

May 2, 2016

Introduction

We’ve been working on the settlement at Must Farm for roughly eight months and have been lucky enough to encounter some of the most exciting Bronze Age archaeology in Britain. One of the biggest elements of the project has been the discovery of several stilted roundhouses, complete with contents, and most importantly: their superstructure. How does our current understanding relate to traditional views of Bronze Age homes?

Before we begin detailing what we currently know about the houses at the Must Farm settlement, there are a few important points to discuss. The relatively unique conditions of the site’s preservation, a combination of fire and water, led to the survival of a huge amount of material both domestic and structural in nature. However, it is critical to remember that despite the very favourable preservation conditions, not everything has survived. We aren’t left with a complete set of components that we can simply refit into a whole roundhouse.

Overview image of roundhouse one, showing the well-preserved but fragmented timbers.

Undoubtedly a portion of the structural timbers will have disappeared as a direct result of the fire. We know that the temperatures of the blaze were very high and the differential charring across the wood assemblage shows many timbers are incomplete. As we are working, it is difficult to estimate exactly how much wood we have lost as a result of the fire. Hopefully, this is a question we will be able tackle with more confidence as we get into the post-excavation phase of the project. Here we’ll be able to see the totals of the timbers on site and also have the valuable input of our forensic fire investigator, Dr Karl Harrison from Cranfield University.

However, there are likely other processes at work which are less obvious related to the survival of certain parts of the structure or its contents. These are difficult to predict and understand during the excavation and, again, may only become apparent once the work on-site has finished. It is possible that there will be parts of these houses that we simply won’t find, even though the preservation across site is generally excellent. It is a difficulty with archaeology and even in the most favourable environments, some information is invariably lost.

This limitation is important to consider as we share our initial theories and findings on the stilted structures. We won’t just be discussing what we currently know about these homes but also what we don’t. This is an important aspect, often absent from archaeological writings, as archaeology involves constantly evolving and refining theories. We don’t always immediately understand every aspect of a settlement and it can take months and years to answer particularly problematic questions. However, we’re a dedicated team and with our specialist support and experience of Bronze Age archaeology in this region we hope to have a very complete picture of the Must Farm settlement at the end of the project’s post-excavation.

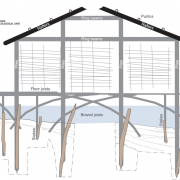

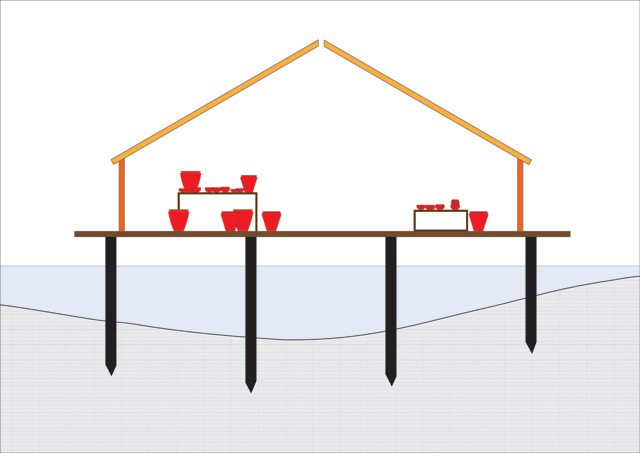

Visualisation to show a stilted house with contents. Over the coming months we’ll be able to refine this image to be much more detailed and accurate.

Building Ground Plans

At the moment we are using roundhouse one as something of a “template” for the other structures. We’ve made the most progress with this house and it is our best preserved building. Doing so will allow us to make comparisons with the other structures and see if their architecture is a match. Looking at the footprints of these buildings reveals some interesting construction details. For reasons listed in previous diaries, we are confident that these houses are stilted homes built above a shallow, slowly moving river.

There are three clear rings of posts that would have formed the basis for the raised buildings, an outer one, an intermediate one and an inner ring. The outer and inner post rings are remarkably uniform. Each upright has a consistent diameter and all are oak. The substantial nature of both these post rings suggest that these timbers formed the principle form of support for the raised element of the homes. Interestingly, the intermediate ring is very different in character. These posts are all much narrower in diameter and are made from ash, rather than oak. Is it possible these were an additional form of support with a different function? Perhaps these smaller, ash uprights could have been a means of supporting the floor of the building?

Image from beginning of excavation showing the initial uncovering of an oak supporting upright.

All the timber uprights are unburnt at this height and were shielded from the fire by being submerged in water. We don’t know, and are unlikely to ever find out, how tall the uprights would have been. This is a consequence of the preservation, any part of the timber protruding above the river level would have rotted and decayed making it impossible to estimate how far above the water the floor of the houses would have been. All the uprights, oak and ash, have been driven very deep into the bottom of the river channel: sometimes in excess of 1.5 metres. This depth is also suggestive that these timbers were designed to support a heavy load.

We also are finding a number of much smaller uprights in the vicinity of roundhouse one. These are made from a currently unknown wood and are clustered around the central ring and, to a lesser degree, around the northern circumference of the house. We don’t know what these small uprights were for at the moment and we’ll have to investigate them much further. However, it is possible that they could be a means of additional support for a currently unknown aspect of the building.

One of the most interesting and unique elements of the houses at Must Farm are their immediate differences between Bronze Age homes from dryland contexts. Typically, the plan of a Bronze Age house is very recognisable with a clear entranceway visible where there is a break in the posts. Often the posts either side of this entranceway are more substantial, presumably to help provide additional support around this gap. However, our raised buildings are symmetrical and there is no clear difference between any of the post rings to suggest an entranceway to the house.

From this simplified image, highlighting all the structural components from roundhouse one, it is not possible to identify an entranceway.

In most prehistoric homes we would expect to find an entrance to the southeast or east of the building. This has been a source of study and research and there is a large body of evidence to support a commonality in the position of doorways in homes from both the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. However, we currently don’t have any clear evidence from anywhere around roundhouse one to indicate where its entrance could have been. The elevation of the structures may make identifying an entrance from the posts impossible.

Thankfully, there may be other methods of working out where people entered and exited their house. When excavating prehistoric settlements, it is often possible to spot a general patterning to material close the entrances of buildings. Often refuse material, such as butchered animal bone and pottery fragments end up being deposited around the entranceway to a house. We are already carefully examining the material deposited around the buildings and will be paying particular attention to any denser clusters of finds. Hopefully, using this form of secondary investigation we can gather some clues about the position of an entrance.

We have many questions still to answer about the plans and formation of the structures. If we are able to identify entrances, will they be orientated in the same direction on each of the structures? Will each building have the same number of posts and will there be three upright post rings for each house? Will the posts from each structure measure similar diameters and will they be driven into the channel at comparable depths?

Related stories

Dig Diary 31: Moving Towards the End of Excavation

May 23, 2016

Dig Diary 27: Pottery

April 25, 2016

Dig Diary 26: Exploring Inside a Bronze Age Home

April 18, 2016

Dig Diary 25: Wooden Objects

April 11, 2016

Dig Diary 24: Visualising the Site

April 4, 2016

Learn more

About

The Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement was excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit with funding from Historic England and Forterra.Publications

Read the Open Access publications the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement: Volume 1. Landscape, architecture and occupation and Volume 2. Specialist reports.Post-Ex Diaries

Our work on-site has finished but lots more investigation is taking place as we study both the material and the evidence we recovered. ...read more

Discoveries

See some of the discoveries from the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement.

Making Must Farm

Find out about our work with AncientCraft recreating Must Farm’s material.

FAQs

Further information on the Must Farm project.