Dig Diary 33: The Palisade and its Construction

June 6, 2016

A Planned Settlement?

In our previous site diary, we discussed our current theory that the duration of occupation at the Must Farm settlement was short. A lack of refuse material, synanthropic insects, construction material being immediately overlain by charred debris and wood being charred whilst fresh all combine to create a picture of a settlement that burnt down not long after its construction. It seems that this was a settlement that had its life cut short by a fire. However, even though we are currently focusing its destruction it is important to consider the construction of this site and the reasons behind it.

The survival and discovery of the Must Farm settlement was the result of good fortune. The depth at which the site was buried alongside the dual benefit of waterlogging and charring ensured this incredible archaeology was preserved to be excavated today. But is Must Farm necessarily an exceptional settlement or could it in fact be just one example of other similar settlements throughout the Fens?

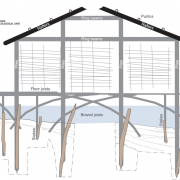

Image showing an investigative slot into the posts related to Roundhouse One. The largest post in the centre is oak and belongs to the outer ring of posts from the structure.

A common interpretation of settlement during the late Bronze Age is that increases in population led to groups moving onto what were considered more marginal lands. One of these areas was the Fens, where limited settlement activity seemed to happen until the Late Bronze Age. Settlement here is sometimes seen as a response: it is regarded as more reactive than proactive. However, gradually over the course of the excavation there is a growing body of evidence that suggests the houses and palisade at Must Farm were the result of careful planning and resource management.

Now that we’ve begun to excavate some of our uprights, including those from buildings and the palisade, we are getting a better idea of the timber that is being used. We’ve known for some time that the building posts are made from oak and the vast majority of the palisade timbers are ash. There seems to have been a conscious choice in the selection of different woods for the various elements of the settlement. Was this choice a result of practicality? Were oak posts preferable for the buildings which required deeper piles and thicker timbers? Could there have been an aesthetic component to this selection of woods, especially the ash that makes up the palisade?

The Palisade and its Construction

We have recently begun to look at the upright posts of both the houses and the palisade and are discovering some interesting results. Since fairly early on in the project, we suspected that the ash used in the palisade came from managed woodlands. Now that we have exposed the entirety of sections of the timbers from the palisade we have more evidence that they came from coppices.

Coppicing is a type of woodland management which is well known throughout prehistory. When many species of trees are cut down, new growths will emerge from the stumps that are left behind. These new growths, termed “shoots” are allowed to grow, a process which will take roughly between 10 and 20 years before they can be cut down and used. When ash is coppiced the new growths tend to form fairly straight poles that are very useful in construction.

Image showing our investigations into a section of palisade. These ash posts are typically driven in to a depth between 1.5m and 2m.

There is often a very distinct, slightly curved shape created at the point where the stump of the tree begins to grow into the new shoots. At the base of our ash palisade posts we have been able to identify this shape that strongly suggests the timber was a result of coppicing practices. What is even more interesting is that this slight curve from the shoot growth has been taken advantage of by the builders of the settlement. When the ends of the timbers have been shaped, the slightly curved area from close to the tree stump has been used to help create the pointed tips needed to drive them into the ground. This seems to have been done to help minimise the amount of time taken to shape each of the tips. Considering there are hundreds of timbers in the palisade, this certainly makes sense.

We are currently in the process of sampling and examining a range of timbers from the palisade. As mentioned in a previous blog, the ring sequences on these ash posts are usually too short to be able to carry out dendrochronological dating on. However, we are still able to compare these shorter growth ring sequences to see if they are the same across multiple timbers. If they are, then this suggests that the wood was all originating from the same, coppiced sources. We won’t be able to get definitive answers from these ring studies until work on site has completed but the results will give us a lot to consider during the post-excavation.

Image of the tips of two ash posts from the palisade. The working of the post tips often reflects the shape created where a coppiced tree shoot grows from a stump.

Planning and Construction: More Questions to Answer

The construction of the settlement here at Must Farm must have been a big undertaking, requiring coordination and planning to successfully complete. We have over 200 posts in the palisade and there would have been at least a similar number in the half that was removed as a result of historic quarrying. There is an enormous degree of uniformity to these ash posts: most have incredibly similar dimensions and shapes. With the evidence of coppicing we are noticing, it seems that most would have come from the same area, or areas, of managed woodland. This is a huge amount of timber, over 400 uprights for the causeway alone, not to mention the hundreds of other pieces required for the houses and their contents.

An image from early on in the excavation showing some of the wood mass. The sheer quantity of wood needed for the settlement would have required careful planning and resource management

It seems that people in the Fenland landscape during the Later Bronze Age were extremely capable if they were able to maintain such large quantities of resources. There are numerous other large-scale timber construction projects going on nearby too, such as Flag Fen, which would have required even more wood. Both ash and oak are trees favour drier landscapes to grow in, yet the Flag Fen basin is well known for being a watery environment. Which raises the question; where were these coppiced woods? Exactly how far was this timber travelling to be used in the settlement here at Must Farm?

However, one of the most exciting questions for us to consider is whether this degree of woodland management suggests there would have been more settlements like Must Farm. Coppicing is a long-term investment, a process which takes years to see the results from. If the timber from the palisade was being grown and managed for 20 years before being used, where were people living in the meantime? Is it really likely that the houses at Must Farm were an isolated, “one-off”?

All of our evidence about the construction of the homes here suggests these were buildings carefully constructed using well-known methods and techniques. Coupled with the emerging evidence for resources prepared years in advance for construction, this suggests that the form, position and building of the Must Farm settlement was not a hasty decision. Given the depth of the site and the fortunate circumstances of its preservation, does this mean there could be many more similar settlements buried throughout the Flag Fen basin? It is a tantalising question and the more we excavate of the site the more likely it seems that many more settlements of this type could be hidden beneath our feet.

Related stories

Dig Diary 35: The Must Farm “Menu"

June 20, 2016

Dig Diary 34: Examining our Clay and Turf Material

June 13, 2016

Dig Diary 33: The Palisade and its Construction

June 6, 2016

Dig Diary 31: Moving Towards the End of Excavation

May 23, 2016

Learn more

About

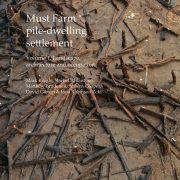

The Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement was excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit with funding from Historic England and Forterra.Publications

Read the Open Access publications the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement: Volume 1. Landscape, architecture and occupation and Volume 2. Specialist reports.Post-Ex Diaries

Our work on-site has finished but lots more investigation is taking place as we study both the material and the evidence we recovered. ...read more

Discoveries

See some of the discoveries from the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement.

Making Must Farm

Find out about our work with AncientCraft recreating Must Farm’s material.

FAQs

Further information on the Must Farm project.