Dig Diary 32: The Lifespan of the Must Farm Settlement

May 30, 2016

Must Farm and the Duration of Occupation

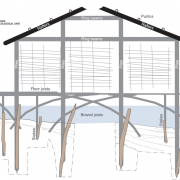

When we discovered the Must Farm settlement one of the first pieces of information we knew was that its life was brought to a dramatic end by a catastrophic fire. The contents of the homes were left behind, the stilted buildings collapsed into the river they were built above and all activity at the site ceased. This was a very definite end to the occupation and this abandonment is clearly visible in the sterile deposits that formed after the settlement’s destruction.

Our picture of this disastrous event is slowly becoming clearer as we excavate, uncovering the burnt debris and remains of the homes here. However, what do we know about the occupation of the settlement before the fire? We are beginning to excavate material from the construction of the palisade and the dwellings, but how long before the blaze was the settlement built? Was this a long-established home for several generations or a new group of houses that’s life was cut short?

Cleaning a fragile wooden bucket-base from the burnt debris beneath a structure.

Material Evidence

One of the biggest indicators for the duration of an occupation at an archaeological site is the presence of the material that is left behind. The quantities of butchered animal bone and broken objects such as pots and querns are usually excellent indicators of how long people were living in a location before moving on. The longer people live in a single place the more food they eat and the more animal remains they discard. Equally, over time pots will break and become worn requiring new ones to be created and the old ones replaced. This leads to the steady creation of waste material and the need to find somewhere to put it. While analysing quantities of artefacts to establish a duration of activity is a long way from an exact science it can give a good estimated timeframe of habitation.

An important consideration to take into account is where waste material was being deposited. Was it being done on site? Close by? On most Bronze Age sites broken and discarded material often ends up in pits or pit groups. However, at Must Farm we appear to have a different method of depositing refuse. In previous blogs we have mentioned how we are finding broken material and butchered bone scattered around the outside of the footprints of the raised homes. This seems to be a result of the occupants of the houses simply throwing any waste or damaged objects outside the building. This material then comes to rest on the bottom of the river channel below in a pattern that respects the shape of the circular structure. Currently, we don’t have any evidence that other refuse was being deposited elsewhere and that the scatters around our houses are likely to be the majority of the waste from the settlement.

Waste material deposited outside the extent of the stilted houses.

What is rather surprising is that we aren’t finding very much refuse material. We have small scatters of pot sherds and butchered animal bone but in terms of the overall assemblage waste appears to make up a surprisingly small percentage. The material around the buildings is in stark contrast to the artefacts we are finding beneath the structures. The assemblages from each building, that still appear to have been in use, are much bigger covering the same styles of ceramics that we find broken. Most of the damaged and broken vessels tend to be the larger storage jars and coarsewares which would have been used more frequently and have a higher chance to break.

This very noticeable difference in the occupation material between “rubbish” and still in use artefacts is leading us towards a conclusion that the settlement was still fairly young in its life when it was destroyed. However, this difference in material quantities, while significant, is not enough on its own to suggest a short lifespan of the settlement. Fortunately, we are getting some interesting environmental and site formation evidence that also supports this theory.

Environmental Evidence

Another key element in the archaeological record relating to the length of an occupation at a site occurs at a much smaller scale than storage vessels and butchered bone. We are taking a large number of environmental samples to be analysed for a huge range of different purposes. One of the goals of our sampling is to look for other signs of human occupation, sometimes on a microscopic level. There are a number of different ways we are doing this but one of the critical methods that can help us understand the duration of an occupation is to look for synanthropes.

Synanthropes are animals and plants that are associated with human occupation. This includes any creatures that benefit from living in close proximity to humans taking advantage of their homes, waste and lifestyles. Particular synanthropes that we are interested in include parasites, such as wood-boring insects, which would certainly have existed within a Bronze Age home. However, when we examined some of our environmental samples from the 2006 excavation we found very little evidence of these creatures.

Environmental samples are incredibly important in understanding the full character of an archaeological site.

These results were especially puzzling as all the other evidence pointed to an established settlement given the quantities of material that we were discovering. Similarly, once we uncovered the scale and extent of the buildings and their contents as part of the current project, this lack of synanthropes was even more mysterious. However, it now seems that their absence could in fact be a consequence of the short lifespan of the homes before they burnt down. The reason for the absence of parasites and other synanthropes could be that they simply didn’t have time to “move in” and start co-existing before the destruction occurred.

We’ve been considering other reasons for the absence of these creatures largely concerning the preservation conditions and formation of the deposits. Did the fire remove all traces of these, both micro and macroscopic? Could the slow moving, shallow water of the river wash away the traces of all synanthropes? Neither of these options seem particularly likely given the preservation and survival of the timber and other microscopic and macroscopic evidence. This area of research is still very much ongoing and examining our current samples from the excavation will provide more evidence to analyse. However, currently this absence of synanthropes appears to support the theory that the settlement had a short lifespan before it was destroyed.

Our timber posts and uprights may have still been relatively fresh when they were charred in the fire.

Another area of evidence is beginning to emerge to support the concept that the settlement had not existed for long before burning down. Recent preliminary examinations of some of the timbers from both the palisade and the houses seems to show that the wood was still fresh when it was charred in the fire. The way in which some of the timber has burnt and the distinct details that are created when charring occurs on a microscopic level could indicate some of the wood was still green when the fire occurred. This is research that is still at an early stage of the investigation and will be understood in much greater detail over the coming months in post-excavation.

As we expand our sampling and analysis of the wood, if much of it proves to still be green when it was burnt this could suggest a very short lifespan of the settlement. When this is combined with the absence of synanthropes and a real lack of occupational waste, the duration of the occupation does seem to have been particularly short.

Site Formation

Another key area of investigation into the duration of the settlement is the formation of the archaeology. When we first investigated the site in 2006 we noticed that there was no gap between evidence of the settlement’s construction and its destruction. Uncharred woodchips from the creation of the palisade sat directly underneath burnt timbers and charred debris with no gap in between. This seemed particularly strange to us as we were expecting a separation as a result of the build-up of both natural river sediments and material from the day-to-day life of the settlement.

Woodchips, like these, from the construction are found directly underneath the burnt material from the settlement’s destruction.

For some time, we assumed that this immediate relationship between construction and destruction was a strange formation anomaly in the deposits of the site. However, upon further exploration of the stratigraphy across the site it now seems that we were seeing a direct representation of the brevity of the settlement’s life. The destruction of the site seems to have occurred soon enough after the construction of the homes and the palisade that there simply was not time for other deposits to form. While it is currently not known exactly how long these layers of sediment would have taken to form within our river channel, examining the deposits on site could help us to understand this timeframe better.

Refining our Understanding

Currently, our evidence strongly suggests that the settlement had a short lifespan. Over the final months of the excavation we’ll be continuing to investigate the relationship between the construction and destruction as we reach the lowest deposits on site. As the on-site work concludes we’ll begin to work on refining more of the environmental data as post-excavation begins. Thinking about the duration of the settlement in this way raises some big questions. An awful lot of time and energy went into the construction of these houses and the enclosing palisade. If the settlement was burnt down soon after the site was built, how and why did this happen? Hopefully, as we get close to the end of the excavation these are questions we’ll start to develop answers for.

Related stories

Dig Diary 35: The Must Farm “Menu"

June 20, 2016

Dig Diary 34: Examining our Clay and Turf Material

June 13, 2016

Dig Diary 33: The Palisade and its Construction

June 6, 2016

Dig Diary 31: Moving Towards the End of Excavation

May 23, 2016

Learn more

About

The Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement was excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit with funding from Historic England and Forterra.Publications

Read the Open Access publications the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement: Volume 1. Landscape, architecture and occupation and Volume 2. Specialist reports.Post-Ex Diaries

Our work on-site has finished but lots more investigation is taking place as we study both the material and the evidence we recovered. ...read more

Discoveries

See some of the discoveries from the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement.

Making Must Farm

Find out about our work with AncientCraft recreating Must Farm’s material.

FAQs

Further information on the Must Farm project.