Dig Diary 34: Examining our Clay and Turf Material

June 13, 2016

Turf, Clay and Scientific Analysis

In the past few months we’ve been busy exploring the lower deposits of archaeology at the Must Farm settlement. These deposits are comprised of a mixture of materials, ranging from artefacts originally from the inside of the stilted structures to the building material used in houses’ construction. In particular, we’ve wanted to understand more about the structural components used in the homes as we have never encountered raised buildings from the Later Bronze Age in this condition.

Two types of material have given us particular pause for thought: large “clumps” of unburnt clay and dark, organic turf-like patches. These materials are always found in conjunction and are often somewhat mixed, though not well, with each type of clump clearly falling into a clay or turf category. In a recent site diary, we described these materials in more detail and how the evidence suggests that they were related to the roofs of the structures. This is still a working theory and we are slowly getting more information as we continue to excavate.

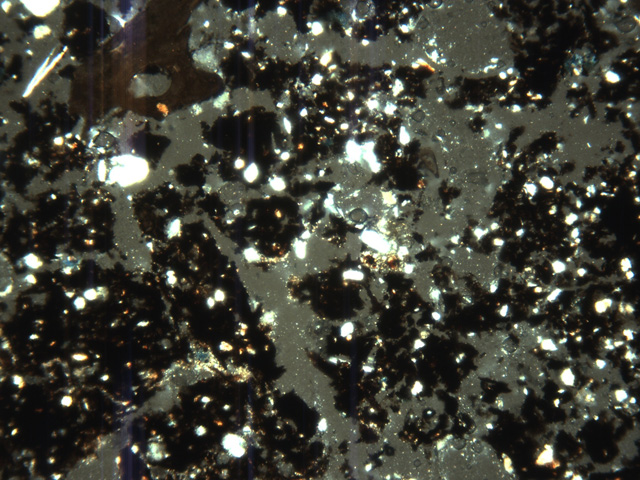

Image showing the clumps of unburnt clay mixed in with turf. They occur over fairly sizeable areas and are often linked to roof timbers.

In the last few days we have begun to get some preliminary results back relating to the clay and turf. Scientific investigation of archaeological material, whether it is artefact, environmental or site formation analysis is absolutely crucial in gaining a more complete overview and understanding. Archaeological analyses are complex processes and selecting samples, transporting them, carrying out preparatory work, conducting the techniques and then interpreting the results is very time-consuming. Often definitive results can be years in the making, however we are delighted to be able to share some of our initial findings as part of the ongoing process.

We are fortunate enough to be working with Professor Charles French, a very experienced geoarchaeologist from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Archaeology and Anthropology. He has worked on a number of extremely important archaeological projects in the Flag Fen basin for over 30 years and his knowledge and understanding of micromorphology is a huge benefit to the project. Archaeological micromorphology involves removing intact blocks of sediments and materials from site, impregnating them with resin, thinning them down to create slides and then studying them through polarized light microscopy.

This process requires significant specialist knowledge and can be used to help identify the character of sediments, providing clues on their origins and what formation processes they may have been subject to. When faced with unusual materials on site that are difficult to understand, such as the clay and turf lumps, carrying out more detailed, scientific analysis is often the best way to begin to understand these deposits.

Preliminary Investigations into Clay and Turf from Roundhouse One

We took a number of samples of both the clay and “turfy” material and the initial results that have come back examining these materials have proved fascinating. On site the colour and texture of the clay-like material initially seemed very similar to roddon material from below the river channel, material that the buildings’ posts were driven into. However, examining the micromorphology of clay samples has revealed that the clay is in fact alluvial and comes from nearby river valleys.

Photomicrograph of the unburnt clay which shows it is a very fine sandy/silty clay ‘grey clay’ (frame width = 4.5mm; cross polarized light). Courtesy of Professor Charles French.

The clay is likely travelling from approximately a kilometre away, in a zone that lies along the edge of the Flag Fen basin. This area is where the wet, marshy environment of the Fens begins and the drier, raised areas of the dryland ends. This is yet another example of the strange, yet dynamic, relationship between the wet and the dry that is really emerging as a major factor of the Must Farm settlement. There are so many strong connections to the dryland emerging from the excavation: cattle, sheep and deer remains, a cart wheel, ash and oak trees from managed woodland on dry ground and now, clay from the drier fringes of the Fens. The Must Farm settlement is clearly not an isolated grouping of buildings in the Fens, there are strong links to the land nearby.

One of the most common suggestions we hear about the presence of this clay is that it was brought in to be used as a raw material for the creation of pottery. However, Charles French’s preliminary examinations, combined with its close stratigraphic connection to the turfy substance, suggest that it was much more probably a building material. Given its close link to many of the roof timbers, we are strongly considering its presence as a component designed to help watertight the roof of the stilted homes. However, there is also a possibility it was used internally, perhaps as a form of “natural, calcitic plaster”.

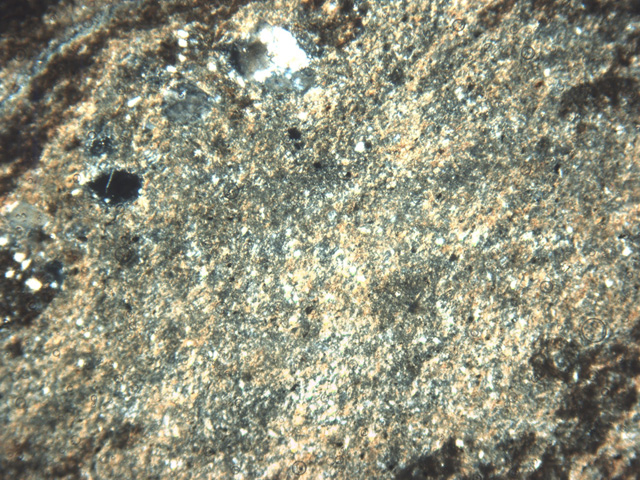

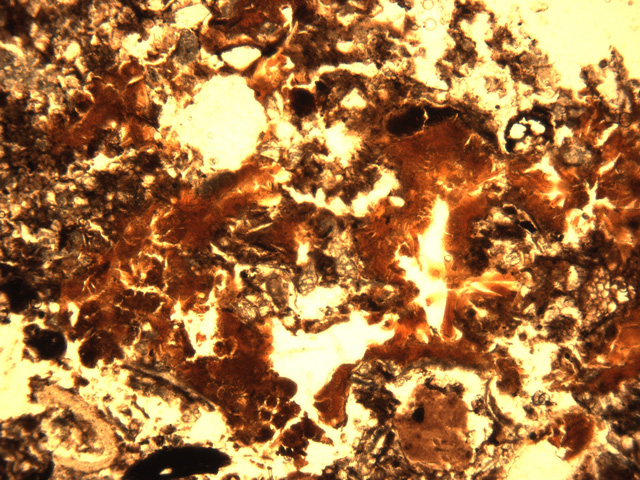

Photomicrograph of turf (frame width = 4.5mm, cross polarized). Courtesy of Professor Charles French.

What is especially clear from analysis is that there is a close relationship between the clay and the dark, organic material. Analysing this organic material reveals that it is definitely turf, as the micromorphs are incredibly similar to other Bronze Age, and even modern-day, turf samples. Interestingly the material contains traces of animal manure and rotting organic material, which are further strong indicators that it is turf.

Photomicrograph of phosphatic-iron compounds in turf, which indicate presence of animal manure and rotted organic material (frame width = 4.5mm; plane polarized light). Courtesy of Professor Charles French.

Dryland Connections?

What is especially interesting is that these clay and turf materials have been encountered before in archaeological excavations that date to the same period as Must Farm within the Flag Fen basin. This kind of clay has been used in the creation of upstanding banks in Bronze Age field systems encountered at the nearby Bradley Fen site, often in conjunction with very similar turf deposits. It seems that these materials were known to people in the Late Bronze Age as materials that could be used in construction.

We know that both the clay and the turf had to originate in dryland, rather than wetland contexts. There is a very important set of features that are well-known from dryland sites dating from the Later Bronze Age in the area where this clay and turf is thought to originate from. Large watering holes are routinely encountered across dryland sites and are thought to act as an accessible source of water for large herds of cattle that would have been kept during this period. Digging a watering hole of this type would not only produce turf, as it would have to be removed before excavation began, but also alluvial clays incredibly similar to those encountered below the buildings at Must Farm.

Could it be that through the creation of these large watering holes that the Bronze Age populations encountered these resources? They would not have had to transport them far, only a kilometre or so, to be able to get them to the buildings being constructed at Must Farm. It certainly makes sense to use relatively local resources to help waterproof and protect your home from the elements. The fact that the turf and clay are so closely related to one another both when they occur naturally and on our excavation is especially interesting.

It is only through understanding an entire archaeological landscape that we are able to make these initial connections. Investigations into the Bronze Age Flag Fen basin and its surroundings has led to truly landscape scale archaeological knowledge. As a result of this we are able to make the comparison between the clay and documented dryland samples of material of the same type. Even though this micromorphological work is still at an early stage, it is already providing us with very useful findings to help inform the excavation process. As more samples are examined, and more scientific techniques are used across the project, we’ll be able to refine and develop our understanding of the settlement even further.

Related stories

Dig Diary 35: The Must Farm “Menu"

June 20, 2016

Dig Diary 34: Examining our Clay and Turf Material

June 13, 2016

Dig Diary 33: The Palisade and its Construction

June 6, 2016

Dig Diary 31: Moving Towards the End of Excavation

May 23, 2016

Learn more

About

The Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement was excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit with funding from Historic England and Forterra.Publications

Read the Open Access publications the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement: Volume 1. Landscape, architecture and occupation and Volume 2. Specialist reports.Post-Ex Diaries

Our work on-site has finished but lots more investigation is taking place as we study both the material and the evidence we recovered. ...read more

Discoveries

See some of the discoveries from the Must Farm pile-dwelling settlement.

Making Must Farm

Find out about our work with AncientCraft recreating Must Farm’s material.

FAQs

Further information on the Must Farm project.